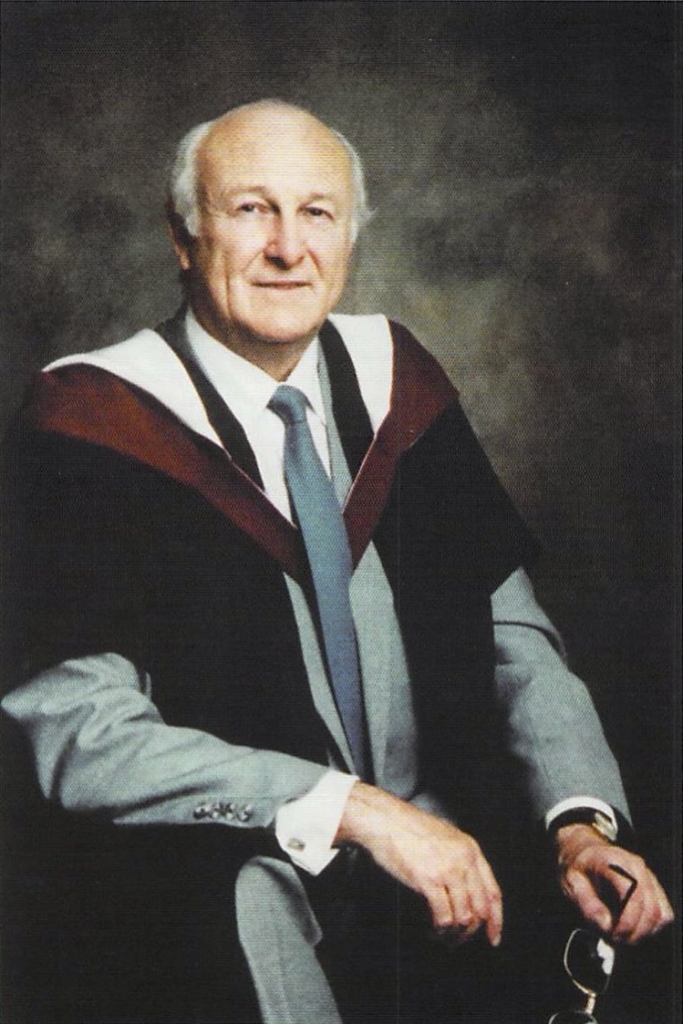

Graham Charlton BDS (Dunelm) 1958, MDS (Bristol) 1970

1928-2020

Graham, was born on October 15th 1928 in Newbiggin by the Sea, Northumberland into a mining family. At first, due to financial constraints, Graham trained as a school teacher at St John’s College, York. He was then called up to National Service in the Royal Ulster Rifles, and was made a Sergeant in the Education Corps in Hanover, Germany.

After a couple of years teaching art, woodwork and games in Morpeth, Graham got a place in 1952 at the Dental School, King’s College, Durham University, situated in Newcastle upon Tyne, then thriving under the Deanship of Sir Robert Bradlaw.

In his first (pre-dental) year Graham needed to fund himself and worked at a bakery in the early mornings before lectures and played semi-professional football in the Northern Alliance League at weekends. He won a state scholarship to fund studies from his second year onwards.

Undergraduate dentistry went well, with Graham taking an active role in student sports and politics and collecting several medals for academic achievement. He married Stella in 1956.

In 1958 Graham graduated BDS and became partner in a general dental practice in Torquay, Devon, where he began to specialise in crown and bridge work. From 1964 Graham returned to academic life at Bristol University to teach Conservative Dentistry, graduating MDS in 1970. The University of Bristol MDS, in addition to being a higher research degree, included a clinical component which was accepted by the Royal Colleges as an acceptable equivalent to the FDSRCS for the award of consultant status. Graham then became the Consultant Senior Lecturer in charge of Conservative Dentistry, and later Clinical Dean. During this time, Graham did the research into the design of post-retained porcelain crowns that led to his MDS dissertation and the invention of the successful Charlton Post – made of stainless steel and with an integrated core. The post itself was cylindrical rather than the customary tapered cast post alternative, and this not only avoided the wedge effect that could lead to longitudinal root fracture, but gave better retention.

In the late 1960’s air-driven handpieces were just becoming available and, whilst other clinical staff thought that they were too dangerous for students to use in their early years, Graham was firmly of the opinion that they should be used from the beginning of operative techniques teaching as they would be the instruments used on patients in the clinic. This was put into practice both in the Op.Techs. Lab and the Cons.Clinic from 1968 onwards, and was a Charlton principle carried forward well after Graham had left Bristol.

Much later, the same principle was used when Bristol became the first Dental School in the UK to teach undergraduates in custom-designed full dental surgeries which could be instantly transfigured to left-handed use if required rather than in the previous tiny cubicles working from instrument cabinets,with materials only available from a central store and no facility for teaching four-handed dentistry.

In the early 1970’s staff accommodation in the Dental School was at a premium and this particularly related to research facilities. The solution was seen to be the renting of accommodation in an adjacent office building (Priory House later to become Manulife House). None of the departments other than Conservative Dentistry wanted to be decanted into a building that necessitated an outdoor walk in all weathers. Graham, however, saw it as the ideal opportunity to establish a proper research facility, and to achieve this end, the putative staff rooms were designed to be minimal in size to leave enough space for the desired research laboratory. Also, Graham had it in mind that if there were to be a future extension on the original Dental School site, the plans would have to include this laboratory and its equipment. This eventually came about with the building of the 1985 extension on Upper Maudlin Street where a whole floor was devoted to staff rooms, a well-equipped laboratory for materials testing, an engineering workshop, a drawing office and a photographic studio/darkroom.

Graham continued his research in the Manulife House laboratory and successfully marketed the resultant Charlton Post and Core. Its success locally was reasonably good, but the requirement for strict instrumentation use plus care and attention to the step-by-step procedure was, in the end, too much for many dentists not blessed with his degree of patience or manual dexterity. He did not suffer fools gladly but was universally liked and admired within the Bristol Dental School.

He often referred to his days at Bristol as the happiest in his life. He lived just outside the city in the beautiful countryside of Backwell with his wife Stella and his three children, and could pursue his precision woodworking, painting and gardening talents to his heart’s content.

Later, when he took up the chair at Edinburgh University in 1978, and also became Dean of Dentistry, he once again raised the standards of dentistry from basic, to above average, and inspired students to pursue excellence in their work. As ever, he encouraged his staff to question all aspects of the accepted wisdom in their researches, as he did himself, and was always happy to contest his thoughts in the national arena. He was never afraid to stand up for his principles when he felt he was justifiably in the right.

Graham continued actively to research dental materials, to teach, and was heavily involved with national professional administration, as well as wasting a great deal of time in planning a new Dental School and Hospital for Edinburgh that, in the end, never became a reality due to last-minute ‘cuts’!

He stood out in that he was not just a brilliant clinician, but could draw on his teaching education to put his expertise across to students in an inspiring and lucid manner. Having ‘come up through the ranks’ as it were, he brought with him an unique individuality of thought and action which set him apart from most of his academic colleagues. He distinguished himself in having all the right qualities for the job and consequently scaled the heights of academic and practical dentistry. He espoused the concepts of Prof Veldkamp of the Netherlands in the design of full gold crowns with reduced occlusal surface width and the ideal hygienic bridge concept, and is also remembered for his whistle-stop tours of the UK to give postgraduate lectures on advanced restorative dentistry. Apart from lecturing, Graham could speak ‘off the cuff’ to great effect, and was often approached to give an after-dinner speech during the meal even without prior notice.

In 1992 Graham retired and moved to Bearsden near Glasgow to help out with his daughter’s newly arrived children and then, as these grew up, moved to York after a gap of fifty years to resume old friendships, and make some new ones.

In 2005 Stella died, and a few years later Graham began to show signs of dementia secondary to cerebrovascular disease. From 2013 he lived in residential care in Newcastle upon Tyne near to his two sons. Graham Charlton died on February 1st 2020 after a series of strokes.

The above illustrates the lasting impression that Graham left on the Bristol and Edinburgh Dental Schools, the staff and the students who benefited from his tutelage, but also how the generations that followed also benefited in the years after he retired.

Geoffrey van Beek

Bruce Charlton

Ken Marshall.